People often think of running as a leg-driven activity, but here’s the truth! Efficient, long-distance running depends on multiple muscle groups working in harmony. Every stride is powered not just by your legs, but by coordinated muscle groups including your core, glutes, hips, and even upper body. These running muscles create a dynamic rhythm that propels you forward with agility, balance, and strength.

Of course, leg muscles like quadriceps, hamstrings, glutes, and calves take the highest impact while running. However, your body also uses core stability muscles to secure your torso, as upper body, shoulder, and arm movements work together to maintain balance. Small stabilizer muscles throughout your feet and hips assist in both injury prevention and performance enhancement while running.

In this comprehensive article, we’ll break down the exact running muscles involved, how they work together, and why running is more than just a cardio workout – it is a total-body challenge.

- Primary muscles worked while running

- Lower body [Main Movers]

Lower Body Running Muscles

The body uses multiple lower-body muscle groups to move, absorb shock, and keep itself balanced during running activities.

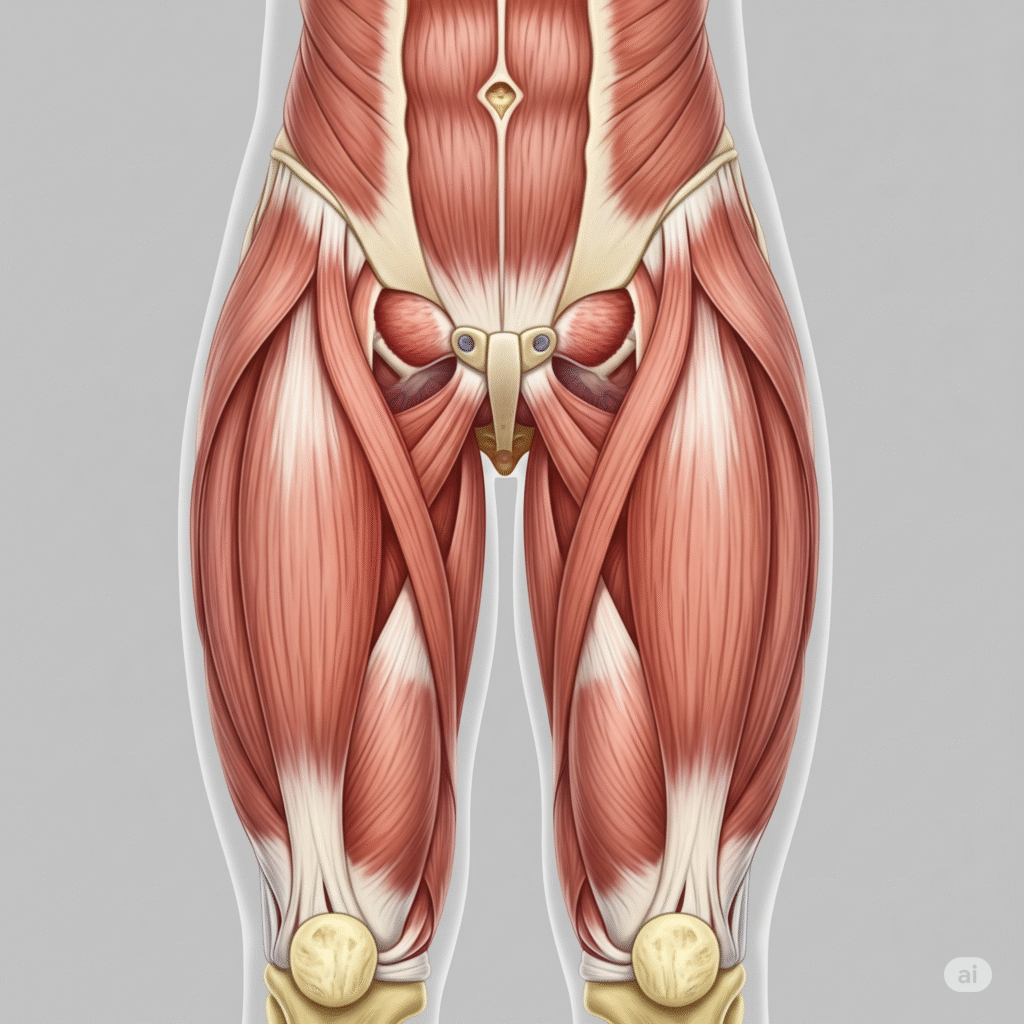

Quadriceps

The four thigh muscles from the front part, known as the quadriceps, serve as the key assets for both knee extension and forward motion. The quads become active when your feet push off the ground because they lift and extend your legs, making them essential for both sprinting and endurance running. Quads are strong muscles and also serve as shock absorbers because they minimize knee stress during impact.

Hamstrings

The hamstrings are positioned on the posterior thigh (back part), and they work to balance the movements of the quadriceps. These muscles enable hip extension and knee flexion during movements, which allow the foot to push back from the ground after foot strikes. After the stride phase, your hamstrings become crucial for producing force and building up speed. You become prone to injuries when hamstrings show signs of weakness and lack sufficient flexibility or strength. You will need focused training to develop strong hamstrings.

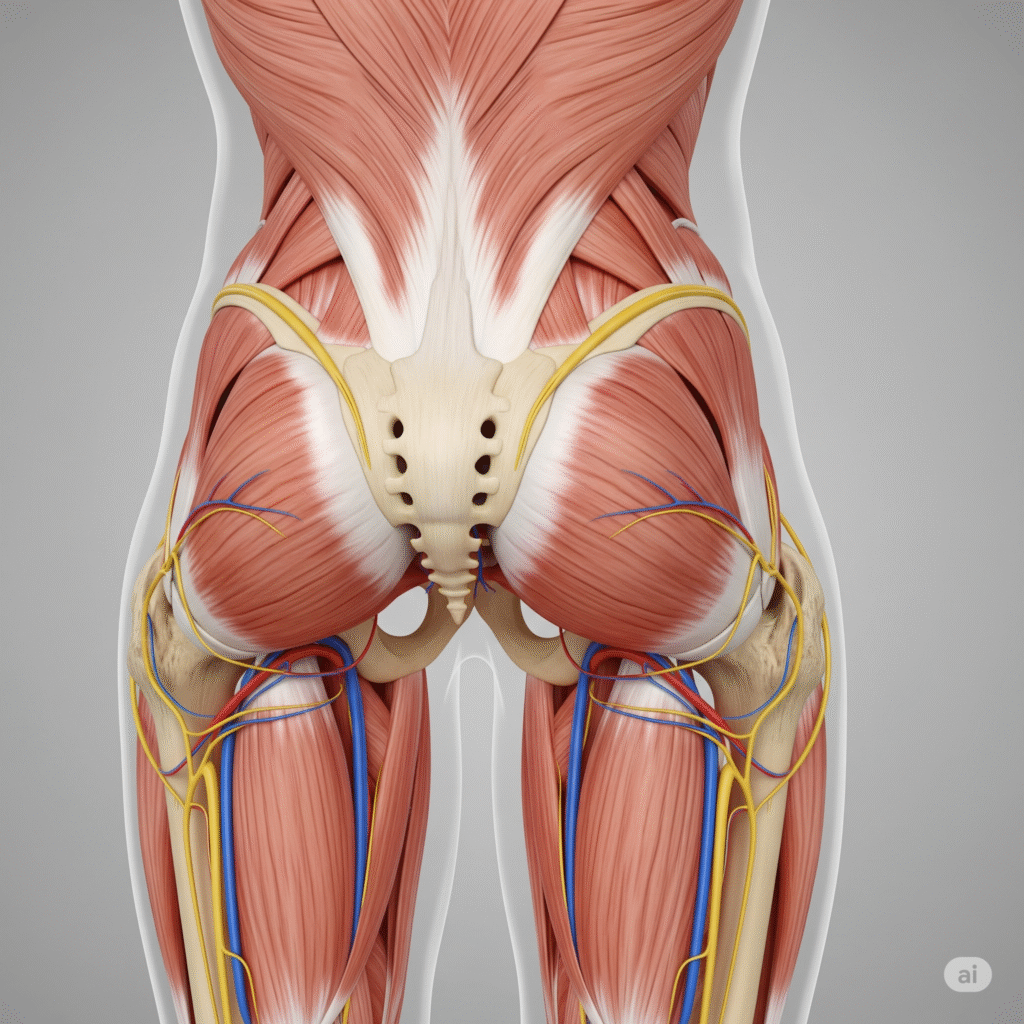

Glutes (Bum muscles)

While running, the gluteus maximus, together with medius and minimus, form the strongest muscles that propel your movements forward. These muscles generate the pressing forces necessary to move forward, maintaining the pelvis’s stability and ensuring a balanced body equilibrium. A strong gluteal muscle system produces efficient running and reduces the risk of a runner’s knee and IT band syndrome.

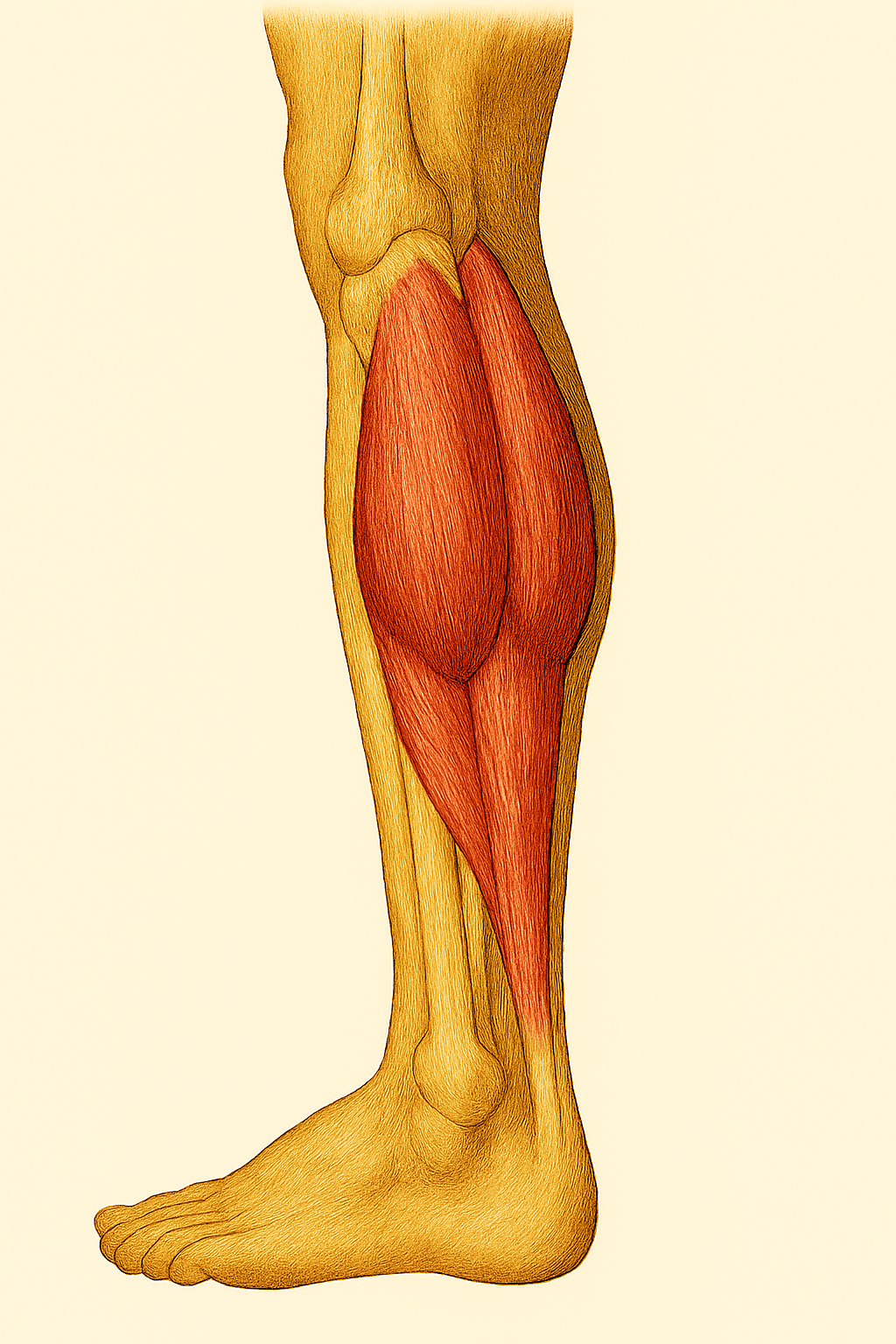

Calves (Gastrocnemius & Soleus)

Running push-off relies heavily on the function of calf muscles. Both the gastrocnemius muscles, which form the visible part of the calves, support explosive movements while running. The soleus muscles, located deeper in the lower sides of the calves, provide endurance capabilities and help to maintain proper balance and posture. The two muscles work together to absorb forces during impact and shield the Achilles tendon from damaging stress.

Core Running Muscles

Even though the leg muscles function the most while running, the core muscles support the stability, balance, and posture. Core strength helps the body to move while avoiding injuries that may arise from irregular body movements.

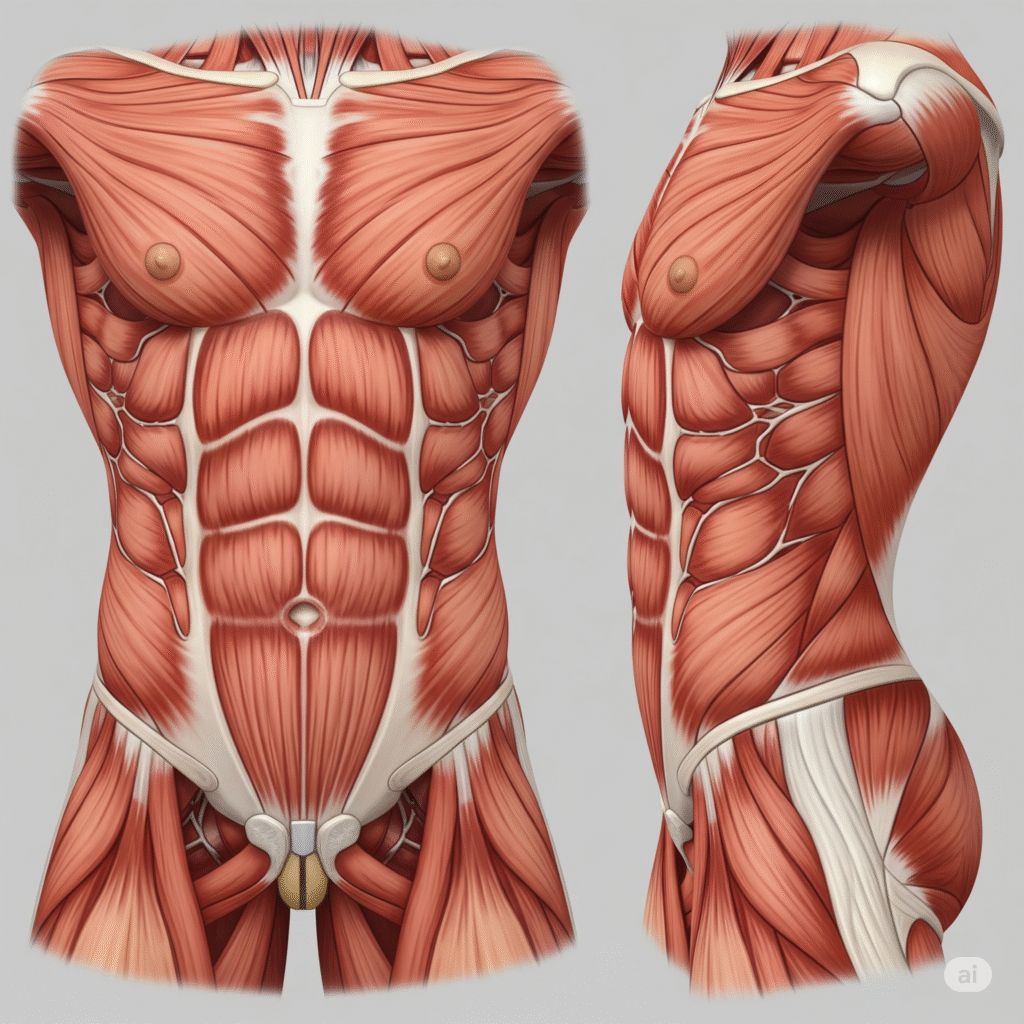

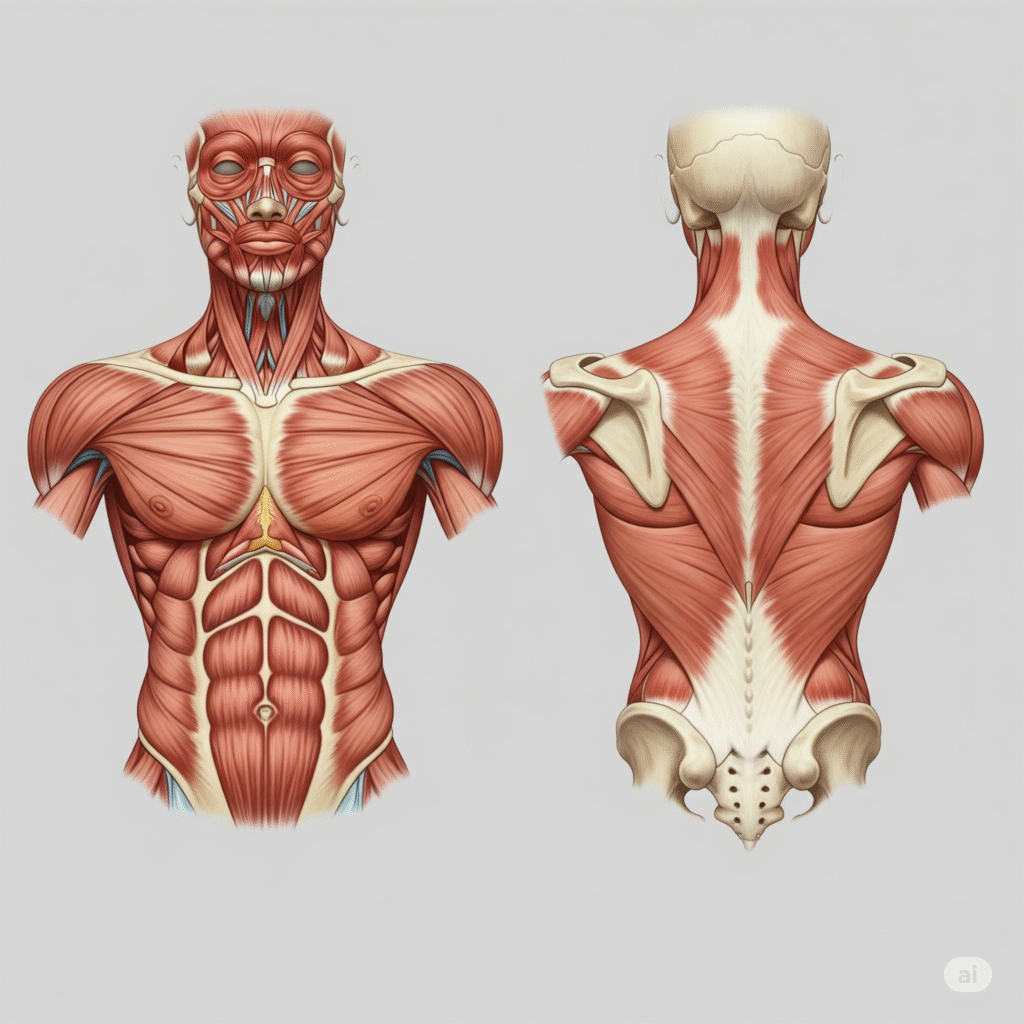

Rectus abdominis & obliques

The rectus abdominis (your “six-pack” muscles), together with obliques (side abdominal muscles), hold your torso straight as they stop your body from slumping sideways. These stomach muscles function as energy transfer points that connect the upper and lower body to produce efficient running movements.

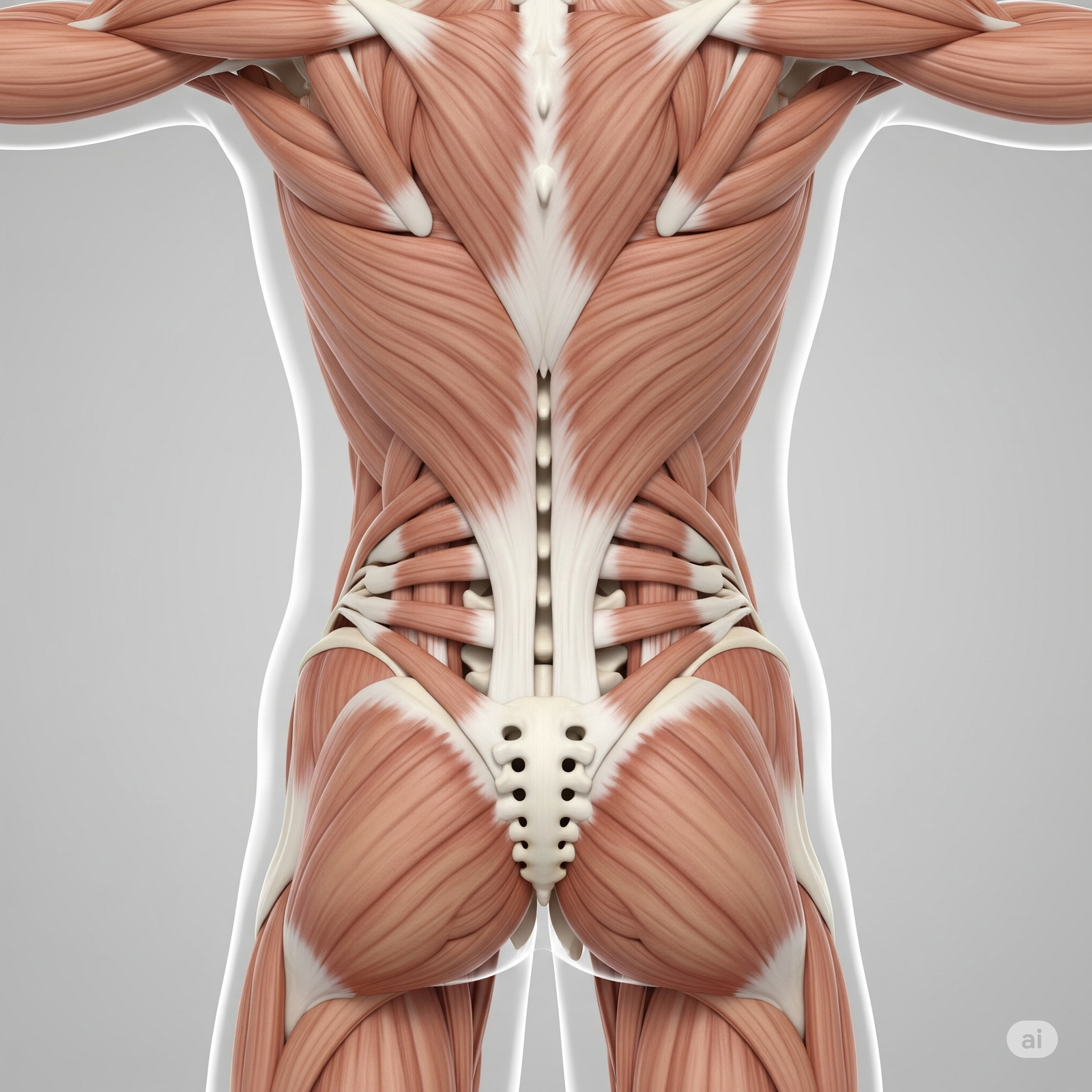

Lower back (Erector spinae & multifidus)

The erector spinae muscles, alongside multifidus muscles, operate as back stabilizers to maintain proper spine alignment and stop abnormal forward-backward body movements. A weak lower back leads to poor posture and back pain, particularly affecting runners who cover long distances.

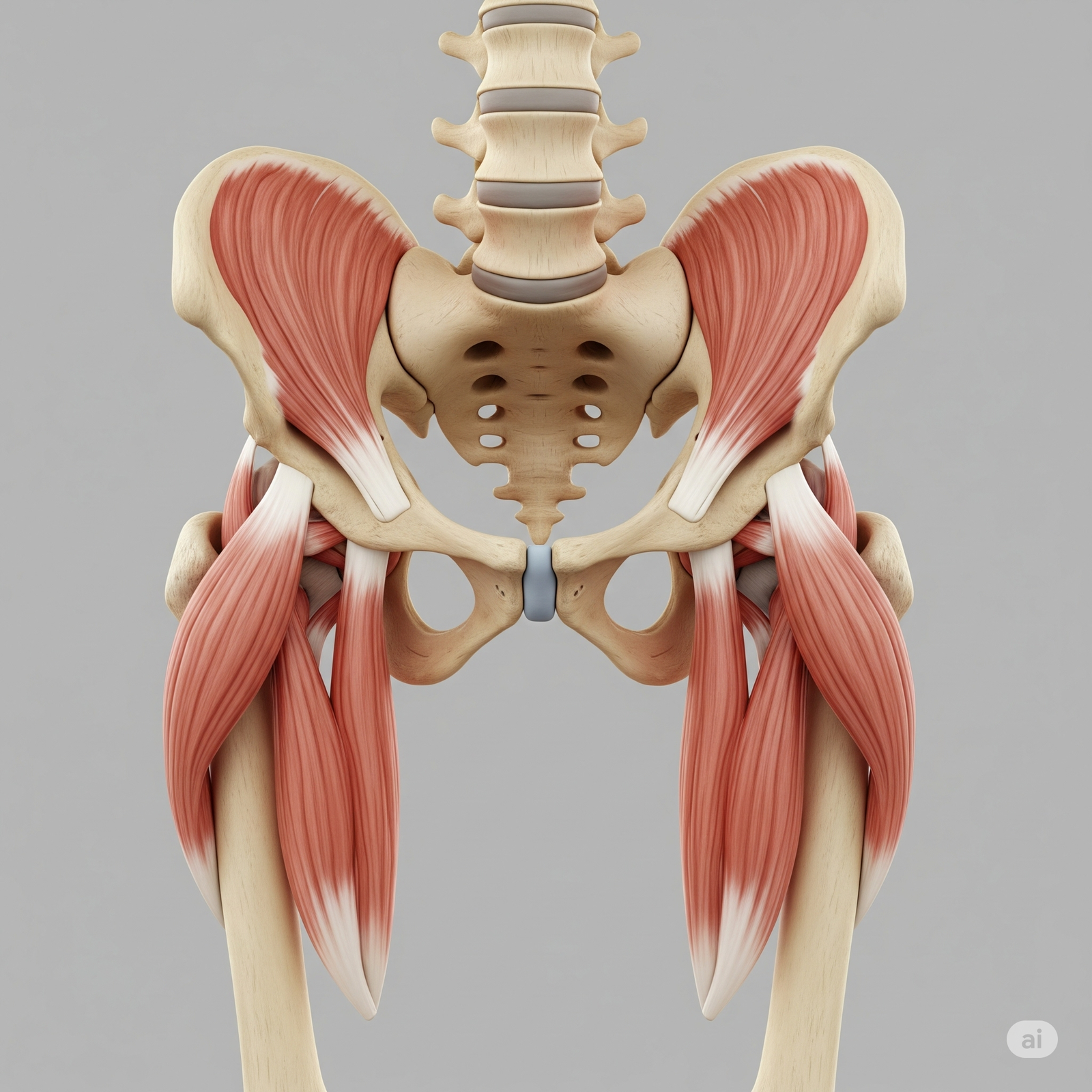

Hip flexors (Iliopsoas, Tensor Fasciae Latae)

The combination of the iliopsoas along with the tensor fasciae latae (TFL) facilitates leg movements, along with the knee lifting function. These muscles work intensely when sprinting uphill while running, but they can become tight because of excessive physical activity, which will decrease their range of motion at the hips. You can loosen them up again with focused stretching and strengthening exercises. That’s why strength and flexibility training are vital for runners to avoid injury setbacks.

Upper Body Running Muscles

The work done by the upper body often goes unnoticed while running, as the legs take center stage. However, understanding the role of the upper body in maintaining balance, building proper rhythm, and achieving technical efficiency can give a boost to your running journey.

Arms (Deltoids, Biceps, Triceps)

Your arms function not only for momentum but also to balance the movements of your legs. The power of shoulder muscles (deltoids) contributes to arm swing movements, and both biceps and triceps provide stability by maintaining proper arm positioning during movements. Strong upper body movements through the arms help runners attain more incredible speed and extended endurance, particularly for sprinting activities.

Shoulders & chest (Pectorals, Trapezius)

Posture stays upright when the pectorals and trapezius muscles work together to avoid excessive slouching. Your body posture plays a big role in the efficiency of your running. It helps you maximize the breathing capacity of your lungs and reduce wasted power and physical exhaustion. You can avoid running injuries to quite an extent by just focusing on your running form, and your chest and shoulders play an important role in giving stability to your posture. Your shoulders and chest muscles are constantly engaged while running, even though not much energy is spent on them.

Supporting running muscles and their role

Several smaller muscles act as stabilizers and hold the end range of motion. They work in sync with the bigger muscles in the leg, core, and upper body and help to prevent injuries, maintain balance, and improve running efficiency. Besides injury protection, they also help in maintaining proper body alignment and making precise adjustments to the dynamic movements.

Stabilizers & Small Muscles

Many runners do not know the essential but small stabilizing muscle groups that aid in controlling movements and minimizing impact on bigger muscles.

- Tibialis Anterior: The Tibialis Anterior, located beneath the front part of your shin, controls foot dorsiflexion and maintains ankle stability during foot contact. Weak tibialis anterior can cause shin splints in runners.

- Foot arch muscles: The intrinsic foot muscles function both to stabilize the arch structure and provide shock absorption. Abnormalities in these muscles can cause both excessive flattening (overpronation) and over-arching (supination), thereby causing knee and hip issues.

- Adductors & abductors: The adductors and abductors give stability to your body while making sideways movements while running. They are located inside and outside of your thighs. These muscles help minimize excessive side movement. Muscular deficiencies in these areas result in joint instability. Runners with this problem can develop IT band syndrome alongside other injuries.

Postural Control

Running activity demands complete body coordination. You have to maintain the form or posture, no matter how tired you are. A strong set of postural muscles enables distance runners to maintain efficient postural position while reducing unnecessary energy usage. These muscles help to resist the gravitational force and maintain proper posture.

- Neuromuscular coordination: Running without a break allows the nervous system and brain to work together for an extended time, thus enhancing the coordination of various muscle groups. Your neuromuscular system continuously becomes more efficient when you maintain the correct form during running activities. Regular running helps to improve your muscle memory and gain high efficiency.

- Endurance in supportive muscles: Supporting muscles need timely contractions to perform optimally, because they work to stabilize the body over extended periods. The ability of these muscles to endure the weight for long hours plays an essential role in stopping muscle imbalances and avoiding fatigue-related injuries.

Impact of running form on muscle engagement

Your muscle engagement while running will show on your running form. If there is something awkward in your form, the chances are you are not engaging some specific muscle groups in the stride cycle. Your form will become efficient if you learn to engage the right muscles with proper timing. You should not feel continuous tension from the same muscle group in your strides.

The energy has to flow from one group to another. Some muscle sets take control while other groups relax for a bit, and all this happens in each stride. The awareness of muscle group activation is particularly helpful for the first few miles. Once you regulate your breathing and get into a nice running rhythm, you don’t think about these split-second things. Your muscle memory will take over from there, and you will be cruising to the finish line. Just be mindful of your overall form till the last stride.

Checkpoints to ensure good running form:

- Stride length: This is an important checkpoint that will help you maintain form. The length should be natural and sustainable for foot positioning while landing, because excessive foot stride leads to knee pain and damage. The length is not always the same; you will have to make dynamic changes while navigating through uneven terrains, slopes, and turns.

- Foot strike: The quadriceps muscles are activated when runners strike their heels during foot contact, whereas the glutes and calf muscles are activated when runners contact with mid-foot or forefoot during strike. Again, the foot strikes can keep changing, but you should be aware of the right muscle group that needs engagement.

- Arm movement: Appropriate arm-swinging motion enhances both rhythm and forward movement, which simultaneously eases lower body tension and provides better overall efficiency. The arms of long-distance runners will have less explosiveness, but they should maintain the right form for longer durations. The hinge at the elbows should be stable, even though you are not using your arms too much to gain momentum. The movement of the arm swing should be straight towards the running direction, and not in a diagonal direction.

The strengthening exercises of supporting running muscles help runners achieve better performance outcomes, decrease their risk of injury, and improve biomechanical balance and stability while running.

Running muscles activation: Sprinting vs. Long-distance

All muscular groups receive activation during sprinting and long-distance running, but the activation patterns differ distinctly depending on speed, duration, and intensity levels.

Sprinting muscles

People who sprint depend on fast-twitch muscle fibers because these produce intense and quick bursts of power.

- Glutes, quads, and hamstrings: The body achieves the fast-forward movement through explosive power generated by the glutes, together with quads and hamstrings. The glutes extend the hips as the hamstrings, along with the quads, generate fast and powerful strides.

- Calves: Sprinters can achieve better acceleration by having their gastrocnemius (main muscle of the calves) provide strong and forceful movements.

- Core & arms: The core functions as a stabilizer for body movement during fast motion, while arm throws from the deltoids, biceps, and triceps to deliver driving momentum.

- Ground reaction force: Sprinting demands stronger muscle activation for more forceful foot contacts and efficient liftoffs from the ground.

Sprinting operates through anaerobic energy production, which generates power from muscle-stored energy instead of oxygen consumption, resulting in faster muscle exhaustion. You will be in either Zone 4 or Zone 5 heart rate zones.

Long-distance running muscles

Even though it is an extended activity, long-distance runners rely on oxygen to generate muscular power, which characterizes aerobic exercise.

- Glutes, quads, & hamstrings: During long-distance running, the glutes and quads, along with the hamstrings, perform sustained movements at reduced effort levels.

- Calves & foot stabilizers: For long-distance runners, the deeper calf muscle known as soleus activates more than the main gastrocnemius, providing shock absorption along with movement steadiness.

- Core muscles: Postural muscles in the abdomen and lower back should stay engaged throughout to protect the body from slouching caused by muscle fatigue.

- Lower arm involvement: Arm movements are essential during long runs for sustainability, but are less forceful when compared to sprinting, which helps in preserving energy for extended durations.

Power-driven speed defines sprinting, since it activates fast-twitch muscles. However, long-distance runners maintain efficiency with heavy use of slow-twitch muscle fibers.

Running Muscles – Conclusion

Running is a total body exercise. Most of the weight-bearing work occurs in the lower body, while the upper body, together with the core, functions to provide stability along with balanced movements. Small stabilizing muscles function to make precise body movements while simultaneously reducing your chances of experiencing injuries. To achieve both high-performance benefits and injury protection during your runs, you need proper alignment of your body combined with appropriate running muscles activation, regardless of sprinting or distance running.

My Take

Now that you know running activates muscles across your entire body, don’t mistake it as a replacement for strength training. The main intention of this article is to highlight that even though your leg muscles do the intensive work, you still need to engage and strengthen the muscles throughout your body. While our legs generate the power during running, the upper body muscles play a vital role in maintaining body balance and control throughout the dynamic movements. Strong muscles around your bones, joints, and ligaments are essential for maintaining good running form, improving performance, and reducing the risks of injury.

Keep in mind, after the age of 30, muscle mass naturally starts to decline. This is why regular strength training becomes a non-negotiable part of your routine, especially if you’re engaging in cardio-intensive activities like running. The only way to counter, or at least slow down, age-related muscle loss is through disciplined and regular strength training. This commitment to your strength training will not only help you maintain muscle mass but also keep you in top form for your running activities.

I recommend at least two to three focused strength training sessions per week for runners, along with dedicated work on mobility and flexibility. These sessions should target key stabilizing muscles, postural control, and joint integrity. I cannot stress this enough: running cannot be your only workout. In fact, relying solely on running can lead to accelerated loss of muscle mass and long-term breakdown. For sustainable progress and injury prevention, your running routine must be complemented with strength and mobility training.