If you’re still running after 40, you should be incredibly proud of yourself. You’ve chosen to keep moving, despite the age-related challenges that many use as an excuse to step away from sports and physical activity. Your resilience in the face of the risk of running injuries sets you apart. You’ve pushed through the doubts, the aches, and the statistics. Only a small percentage of people continue running into midlife and beyond, so take a moment to recognize your dedication, grit, and commitment to your health. You’re not just defying age stereotypes; you’re rewriting them.

Many people avoid running after 40 due to the fear of injuries. It’s true, our bodies become more vulnerable to strain and impact as we age. But that doesn’t mean you need to give up running or give up on fitness altogether. Avoiding physical activities might seem like a safe choice, but it can do more harm than good in the long run. If running isn’t your thing, that’s okay. Choose a sport or training style that suits your body and interests. What matters most is staying active. Because after 40, a sedentary lifestyle isn’t just limiting; it’s an open invitation to pain, stiffness, and preventable health issues. Remember, staying active is the key to a healthy and fulfilling life.

Common running injuries can be prevented

The truth is, most common running injuries can be prevented with smart training strategies and proper recovery practices. By learning how to train intelligently, you can continue improving your health and fitness while minimizing injury risk. Let’s explore the most common running injuries faced by adults over 40, and also the practical ways to avoid them so you can keep moving for years to come. Remember, with the right knowledge and approach, you can overcome these challenges and continue your running journey.

Common Running Injuries

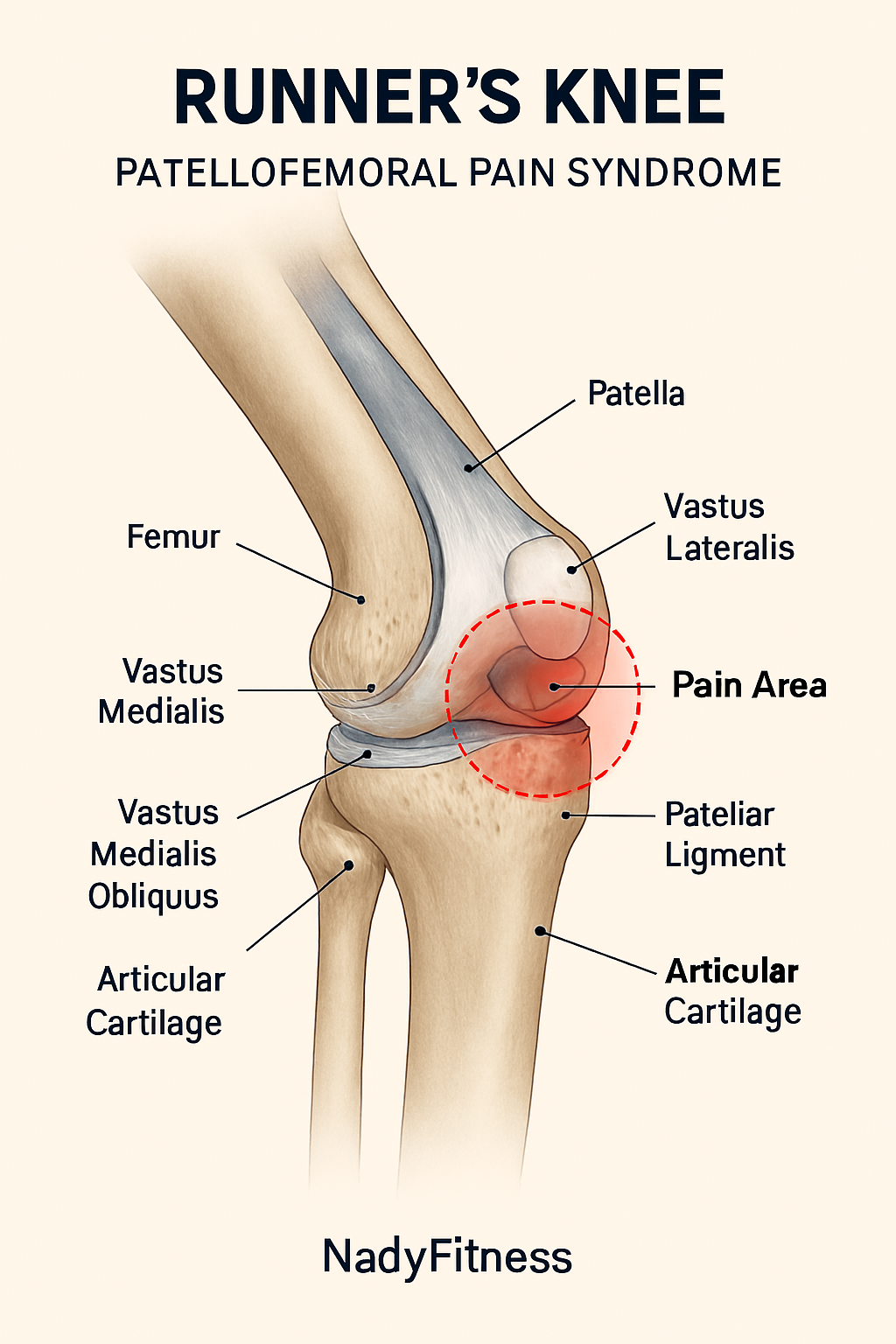

Runner’s Knee (Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome)

Description

Runner’s Knee, medically known as Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome (PFPS), is characterized by pain around or behind the kneecap. It’s a common injury affecting runners of all ages. The pain typically worsens during squatting, stair climbing, or after sitting for extended periods with bent knees.

Runner’s Knee, or Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome, is a condition in which the articular cartilage on the underside of the kneecap becomes irritated, inflamed, or degenerates due to repetitive stress from activities like running, jumping, or squatting. It can be triggered by factors such as muscle imbalances, structural misalignment, and poor movement biomechanics. Additional contributors include improper footwear, hard running surfaces, and age-related cartilage degeneration, which can reduce joint resilience over time.

Prevention and Healing

- Strengthen the quadriceps, especially the VMO (Vastus Medialis Oblique)

- Include glute and hamstring exercises to support knee stability

- Avoid downhill running temporarily to reduce patellar stress

- Reduce running distance if pain intensifies

- Use foam rolling on the IT band and quadriceps to release tension

- Apply knee support or patellar taping if the knees feel unstable

Plantar Fasciitis

Description

Plantar fasciitis is an overuse injury involving inflammation or microtears in the plantar fascia, which is a thick band of connective tissue that runs along the bottom of the foot, connecting the heel bone to the toes. People often notice sharp heel pain or stiffness when they first get out of bed or stand up after sitting for a while. The discomfort can worsen with toe flexing, long periods of standing, or walking on hard surfaces. While movement may ease the pain temporarily, it often returns after rest or overuse.

Prevention and Healing

Healing and prevention involve a combination of mobility, support, and strengthening strategies:

- Stretch regularly: Focus on the calf muscles and the plantar fascia itself to reduce tension.

- Use supportive footwear: Orthotics or arch supports can help distribute pressure and reduce strain.

- Apply ice massage: Rolling a frozen water bottle under the foot can soothe inflammation and ease pain.

- Strengthen foot muscles: Strengthen the intrinsic muscles of the foot to improve arch support and resilience.

- Limit hard surface exposure: Avoid spending excessive time on concrete or other hard surfaces to reduce impact stress.

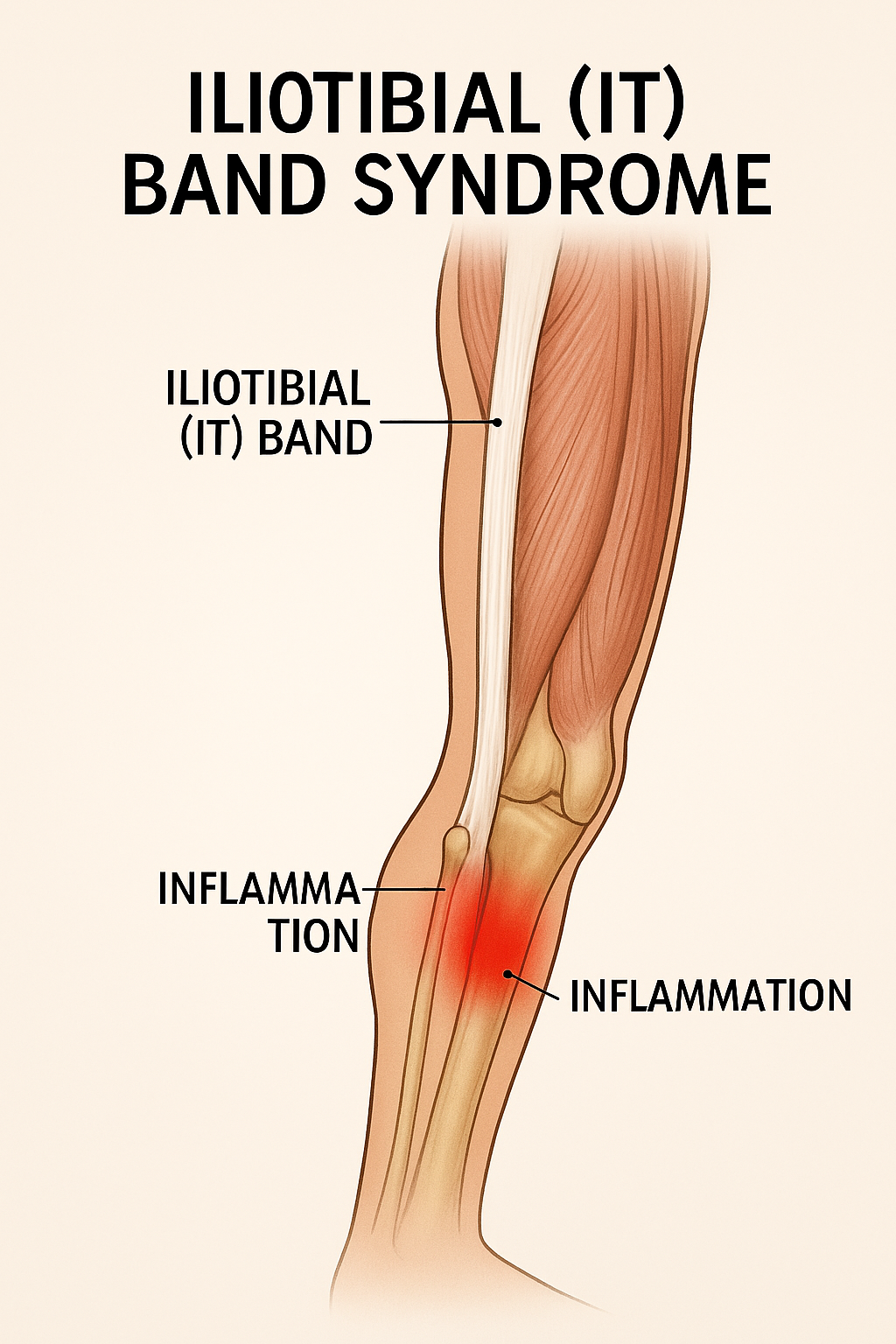

Iliotibial (IT) Band Syndrome

Description

IT Band Syndrome is characterized by pain on the lateral (outer) side of the knee, often triggered by downhill running or long-distance efforts. The pain results from friction between the iliotibial band and the lateral femoral epicondyle (outer thigh bone). You may also feel tenderness along the outer thigh, especially when the knee is flexed to approximately 30°, a hallmark diagnostic cue.

Prevention and Healing

- Strengthen the hip abductor muscles, particularly the gluteus medius.

- Incorporate lateral leg raises and hip-opening stretches for rehabilitation.

- Use foam rolling on the IT band and Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL) to release tension.

- Avoid running on slopes until tenderness subsides.

- Reduce stride length and increase cadence to minimize joint stress.

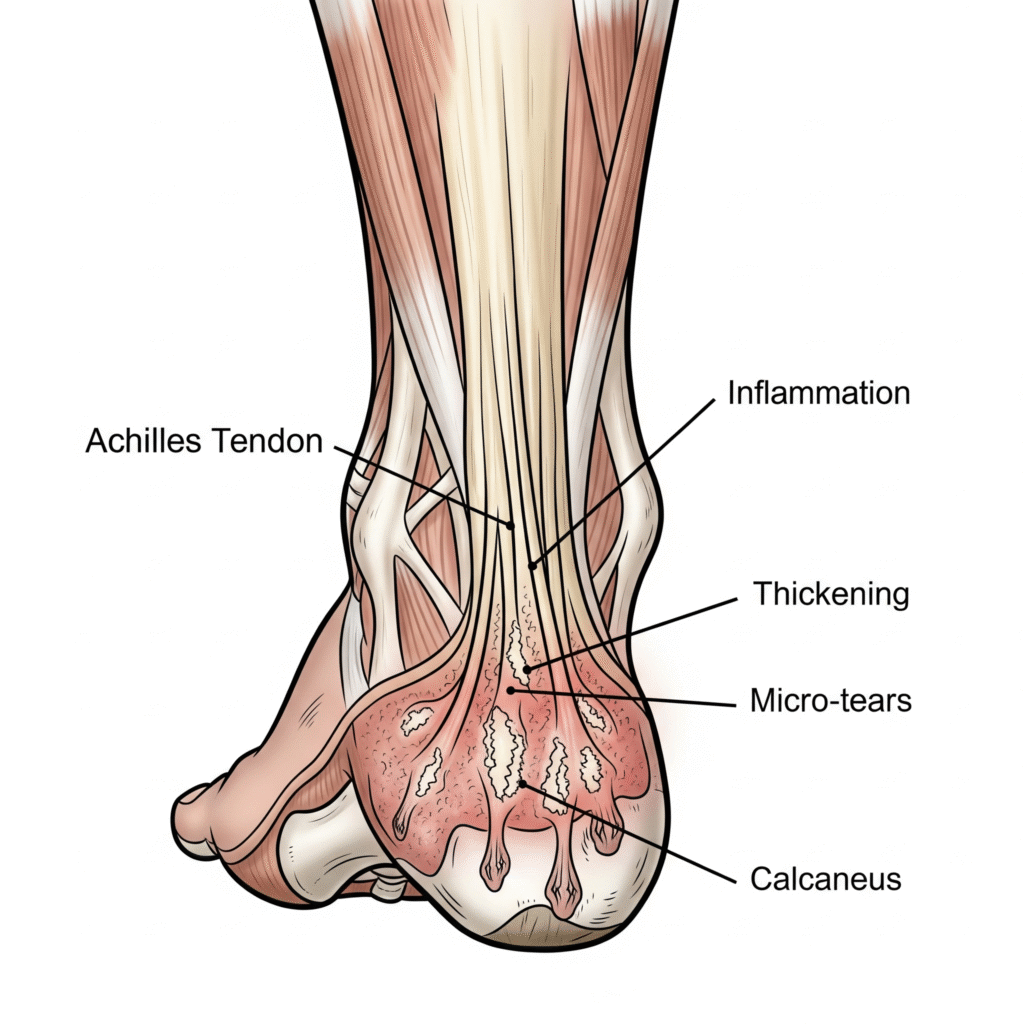

Achilles Tendinopathy

Description

Achilles Tendinopathy is marked by stiffness and inflammation of the Achilles tendon, located at the back of the heel. Pain is often worse in the morning and tends to ease slightly as the day progresses. Tenderness and discomfort typically occur just above the heel, especially during toe raises. This condition can result from prolonged poor running posture, particularly on slopes, and is often aggravated by improper footwear.

Prevention and Healing

- Perform eccentric heel drops (Alfredson protocol): slow, controlled lowering movements to strengthen the tendon.

- Try the half-lunge with imaginary wall push stretch in the front to relieve tension.

- Include calf stretches and strengthening drills in your warm-up routine

- Avoid hill running and sudden increases in training intensity

- Maintain proper running posture to reduce tendon strain

- Use heel lifts or shoes with adequate arch support to offload the tendon strain.

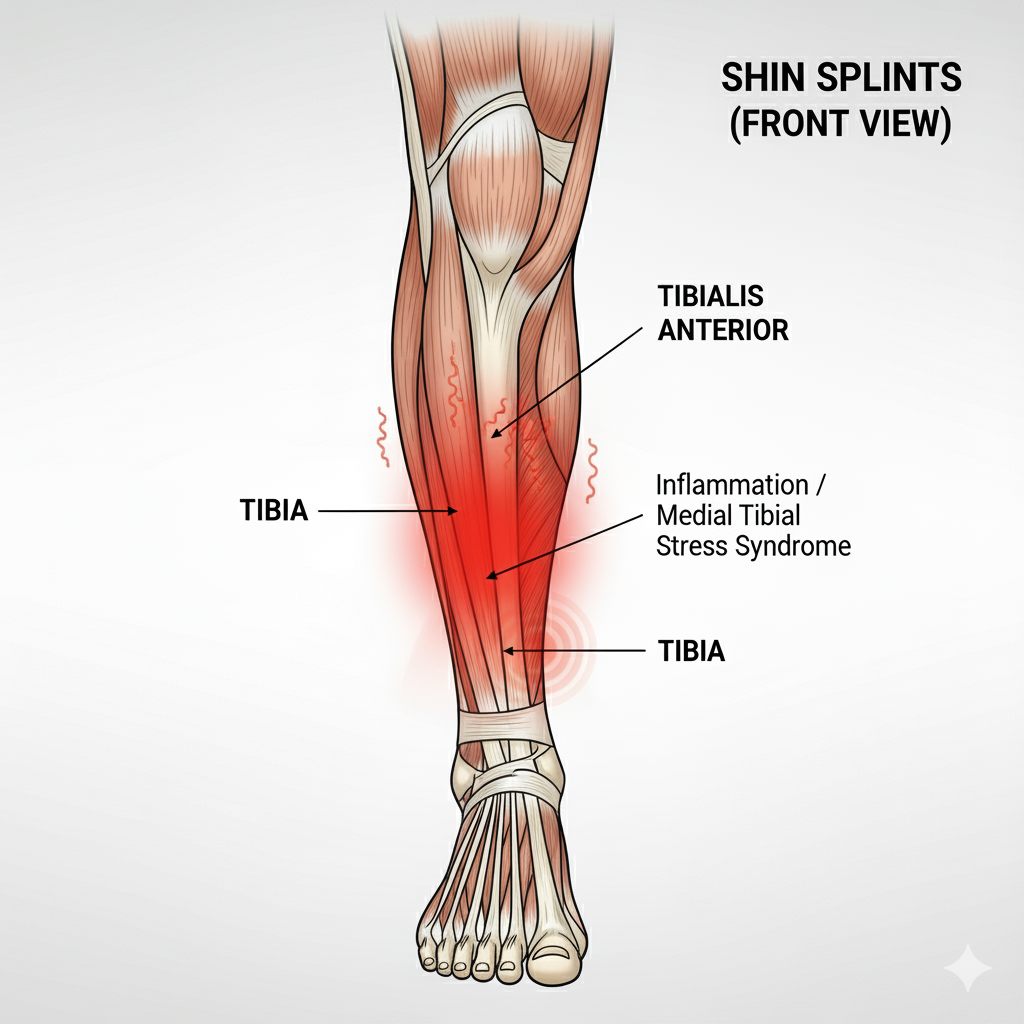

Shin Splints

Description

Also known by its medical name, Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome (MTSS), this condition causes pain along the inner edge of the shinbone (tibia). It typically results from inflammation of the muscles, tendons, or bone tissue in the tibial region due to repetitive stress. The pain is often diffuse; meaning you may feel it along the tibia but struggle to pinpoint its exact source. Even a small accidental impact on the area can trigger sharp, excoriating pain.

Prevention and Healing

- Rest for a few days to allow inflammation to settle. Maybe 2-3 days.

- Reduce running distance and speed until pain subsides.

- Maintain proper running form and avoid overcompensating with the uninjured leg.

- Incorporate strength training for both the anterior and posterior tibialis muscles.

- Check for overpronation: Uneven wear on your running shoes may indicate an arch collapse. I’ve broken this down in detail in my post on pronation issues in runners, so feel free to dive deeper there.

- Apply ice packs and use light massage post-run to ease discomfort.

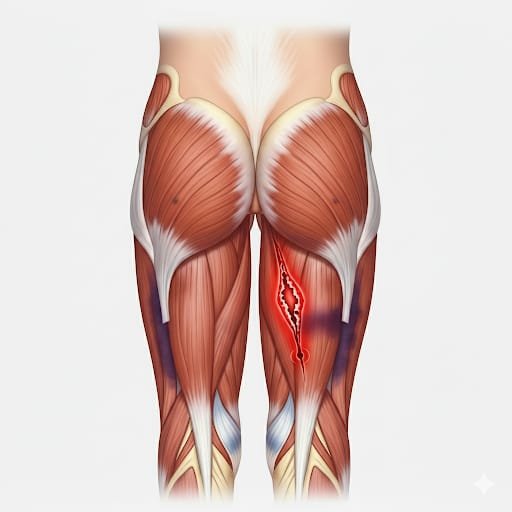

Hamstring Strain

Description

Hamstring strain is more common in older adults and often occurs during sudden bending or overstretching of the hamstring muscles. Runners may also experience this injury when abruptly increasing training intensity. Pain is typically felt in the back of the thigh, especially when flexing the knee. Tenderness is often present upon touching the affected area

Prevention and Healing:

- Allow the tenderness to settle for a few days before resuming your fitness activity.

- Perform gentle quadriceps stretches to reduce tension across the pelvis.

- Begin with isometric hamstring exercises to activate the muscle without strain.

- Progress gradually to eccentric loading (e.g., Nordic curls or controlled heel drops).

- Avoid sudden increases in running speed until the hamstrings are pain-free and stable.

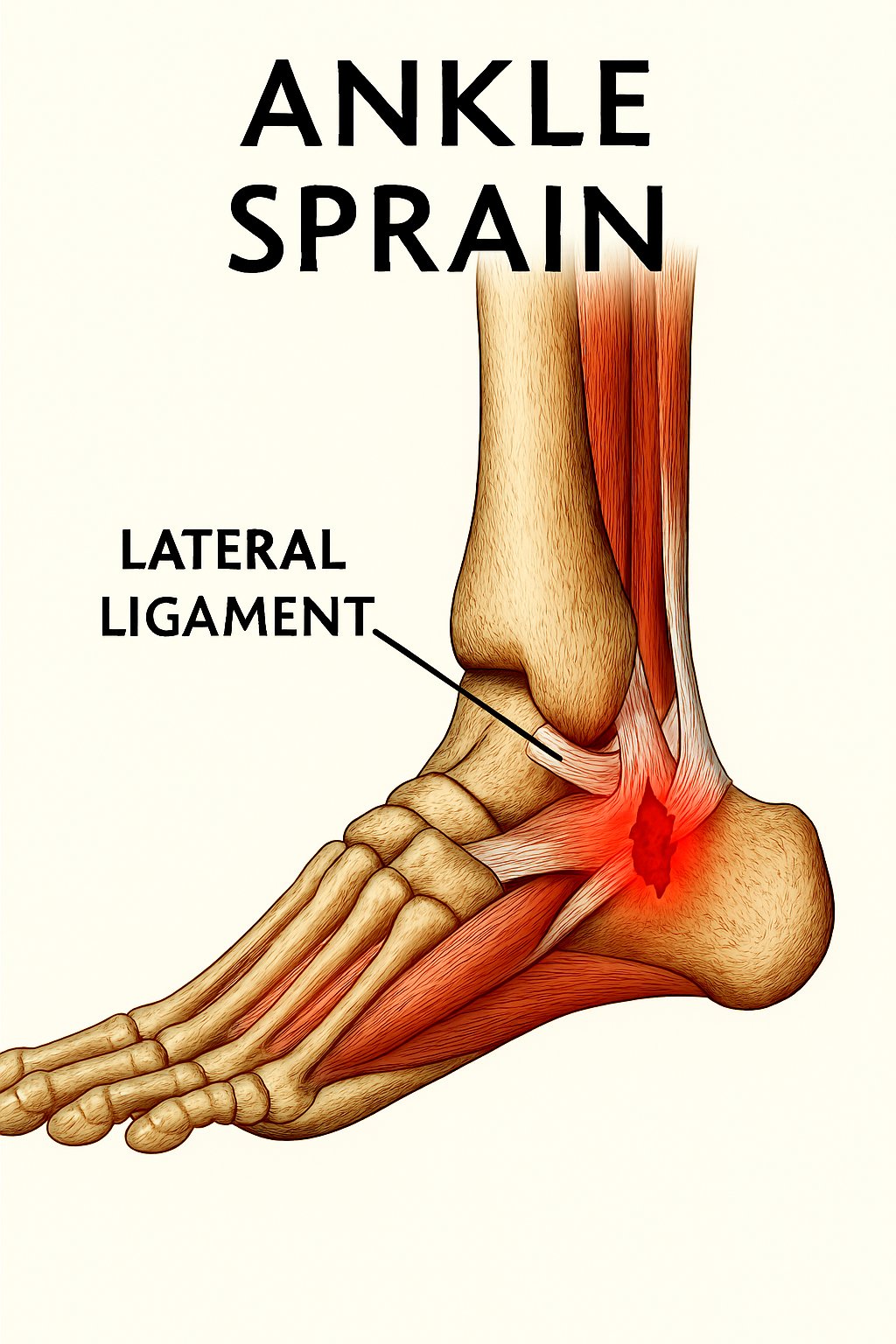

Ankle Sprain

Description

An ankle sprain is a common running injury that typically occurs when you twist or roll your ankle due to an unstable foot strike or uneven terrain. The first few minutes after the ankle sprain injury are often extremely painful, followed by swelling and possible bruising over the next few days, depending on severity. Range of motion becomes limited, and pain is usually felt on the lateral (outer) side of the ankle with each step. You may have to pause their running routine for a few days.

Prevention and Healing:

- In mild cases, you may return to light running within a week, but full rehabilitation and strengthening can take several weeks to a couple of months.

- Rest for a few days and apply ice packs; gentle massage with pain-relief cream and heel elevation can help reduce swelling.

- Begin walking once the swelling subsides, usually after a few days.

- A good test to check your readiness is with heel walking: If you can take 10-15 steps without pain, your body may be ready for short, slow runs.

- Swelling may persist but avoid overcompensating with your uninjured ankle to prevent secondary injury.

- Include balance and proprioception drills to restore ankle stability.

- Use resistance bands for targeted ankle strengthening.

- Wear an ankle brace during daily activities for added support until pain and instability resolve.

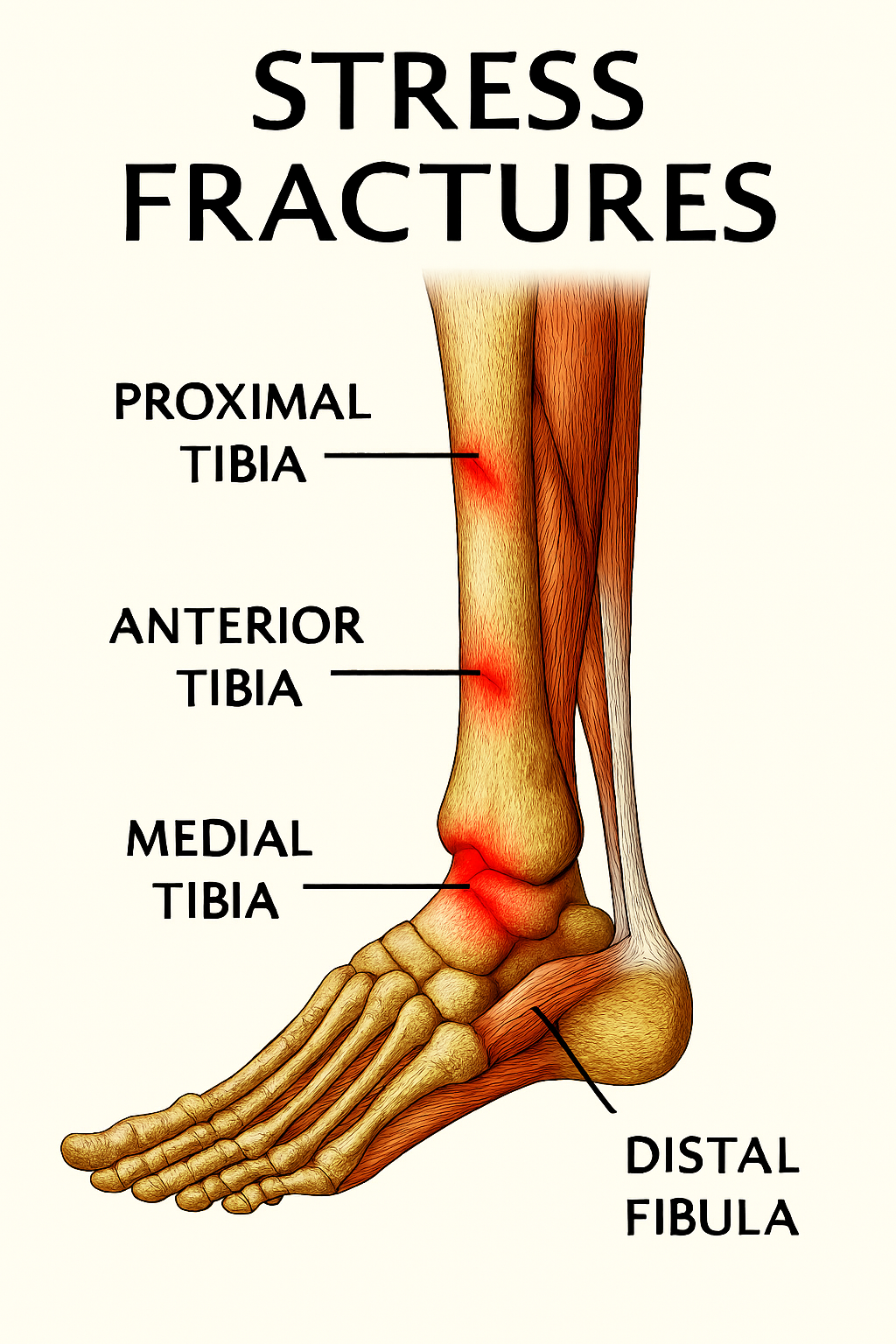

Stress Fractures

Description

Stress fractures are a classic example of overuse injuries in runners, involving damage to bones that range from tiny cracks to severe bruising. The most commonly affected bones include the shinbone (tibia), foot bones (metatarsals), and occasionally the femur, navicular, or fibula.

These injuries occur when fatigued or weakened muscles fail to absorb impact, transferring excessive force directly to the bone. Runners are especially vulnerable when training on hard surfaces without proper footwear, or when increasing mileage or intensity too quickly without adequate muscular and joint preparation. Individuals with low bone mineral density or osteoporosis are also at higher risk. Biomechanical imbalances, such as overpronation or poor running form, can further contribute to stress fracture development.

Pain is typically localized and worsens during weight-bearing activities, whether in the gym or during daily movement. The affected area may be tender, swollen, and in severe cases, show visible bruising. While rest may temporarily relieve symptoms, pain often returns with activity. Diagnosis is confirmed through X-rays or MRI scans, but the early-stage fractures may not be visible on standard imaging.

Prevention and healing

- Rest: Recovery is a crucial part of the healing process. For severe cases, it may require 6–8 weeks of rest, while milder fractures may heal faster.

- Activity Modification: Reduce weight-bearing on the injured area; crutches or orthopedic boots may be needed for high-risk fractures.

- Gradual Return: Resuming fitness after a stress fracture is a delicate process. It’s best done slowly, ideally under professional supervision, to avoid relapse.

- Progressive Loading: Begin with low mileage and increase by no more than 10% per week.

- Footwear: Use supportive, cushioned running shoes and replace them regularly.

- Strength Training: Start with low-intensity exercises and gradually build muscle around the affected area.

- Nutrition: Ensure adequate intake of vitamin D and calcium to support bone health and healing.

- Monitoring: Older runners and those with a history of fractures should regularly assess their bone health. This proactive approach allows you to identify and address any weaknesses before they lead to a stress fracture.

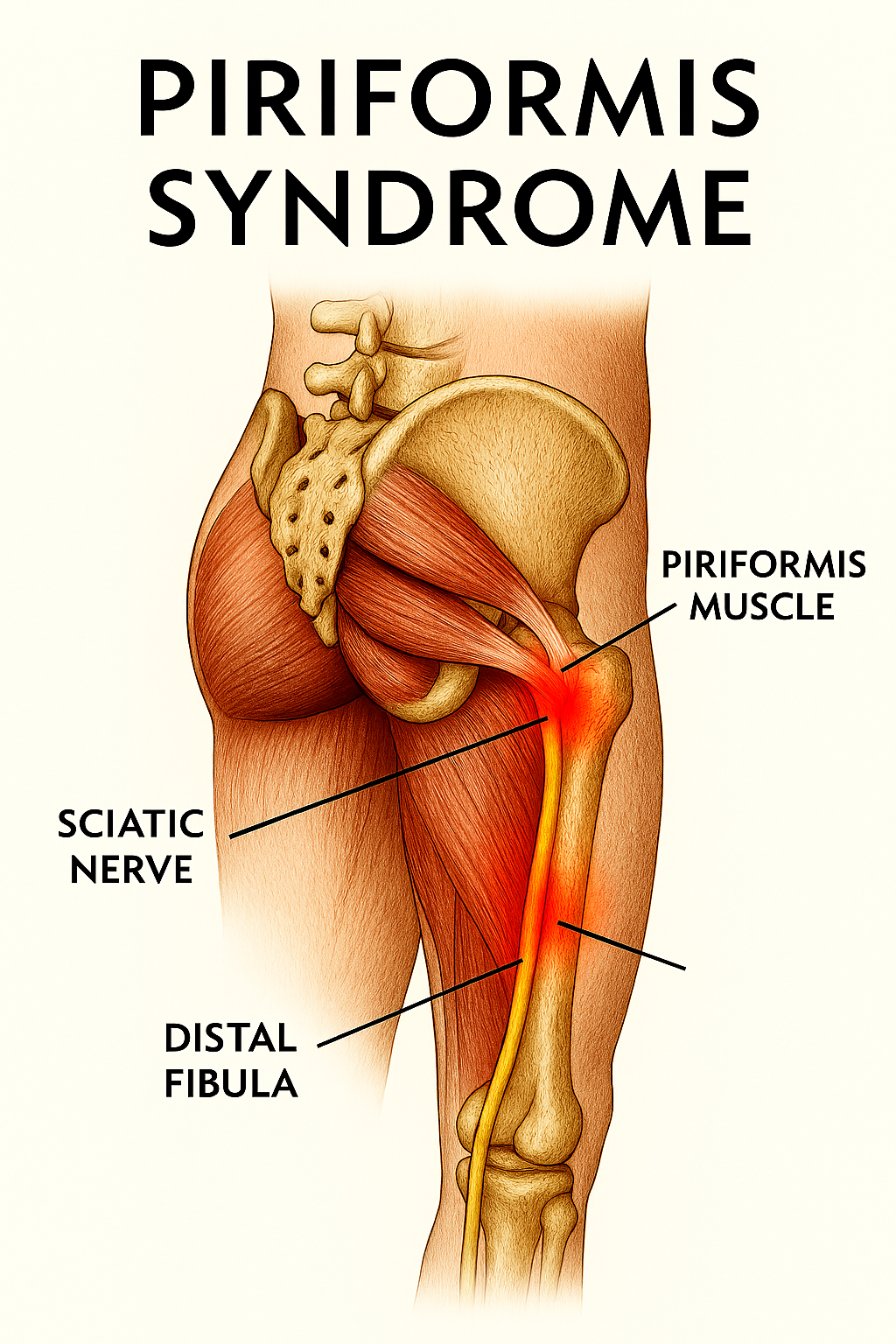

Piriformis Syndrome

Description:

Piriformis Syndrome, a neuromuscular condition commonly observed in runners, is caused by tightness, inflammation, or spasms in the piriformis muscle. This muscle, deeply seated within the gluteal region, is crucial for hip rotation and pelvic stabilization, thereby playing a pivotal role in maintaining the correct running form. Factors such as poor running mechanics, sudden increases in training intensity, and weak glutes can lead to piriformis strain and sciatic nerve irritation.

Piriformis Syndrome occurs when the sciatic nerve, which usually runs beneath or, in some individuals, through the piriformis, becomes compressed. This compression can cause radiating pain, spasms, numbness in the legs, or tingling sensations that travel from the buttocks down the back of the leg. Symptoms may worsen with prolonged sitting, uphill running, or stair climbing. Older adults, due to reduced muscle mass, tighter connective tissues, and sedentary habits, are more susceptible. Those whose sciatic nerve passes through the piriformis muscle are at a higher risk of developing this condition.

Piriformis Syndrome, often mistaken for sciatica due to similar symptoms, is a distinct condition. Unlike sciatica, which is caused by a herniated lumbar disc, Piriformis Syndrome originates from nerve irritation within the gluteal region.

Prevention and healing:

- Stretching: Regular flexibility work targeting the hamstrings, glutes, and hip rotators can aid both rehabilitation and prevention.

- Strength Training: Focused glute activation reduces strain on the piriformis and prevents compensatory overuse of surrounding muscles.

- Warm-Ups: Always include dynamic warm-ups before running to prepare the hip stabilizers, especially if you are running on uneven terrains like trails and uphill runs.

- Movement Breaks: Avoid prolonged sitting. Incorporate standing intervals or mobility drills to reduce stiffness and improve circulation.

- Soft Tissue Work: Use foam rollers or massage therapy to release tension in the piriformis and surrounding fascia.

- Nerve Flossing: Sciatic nerve mobilization drills can relieve pain and improve range of motion. These should be performed under the guidance of a qualified physiotherapist or trainer.

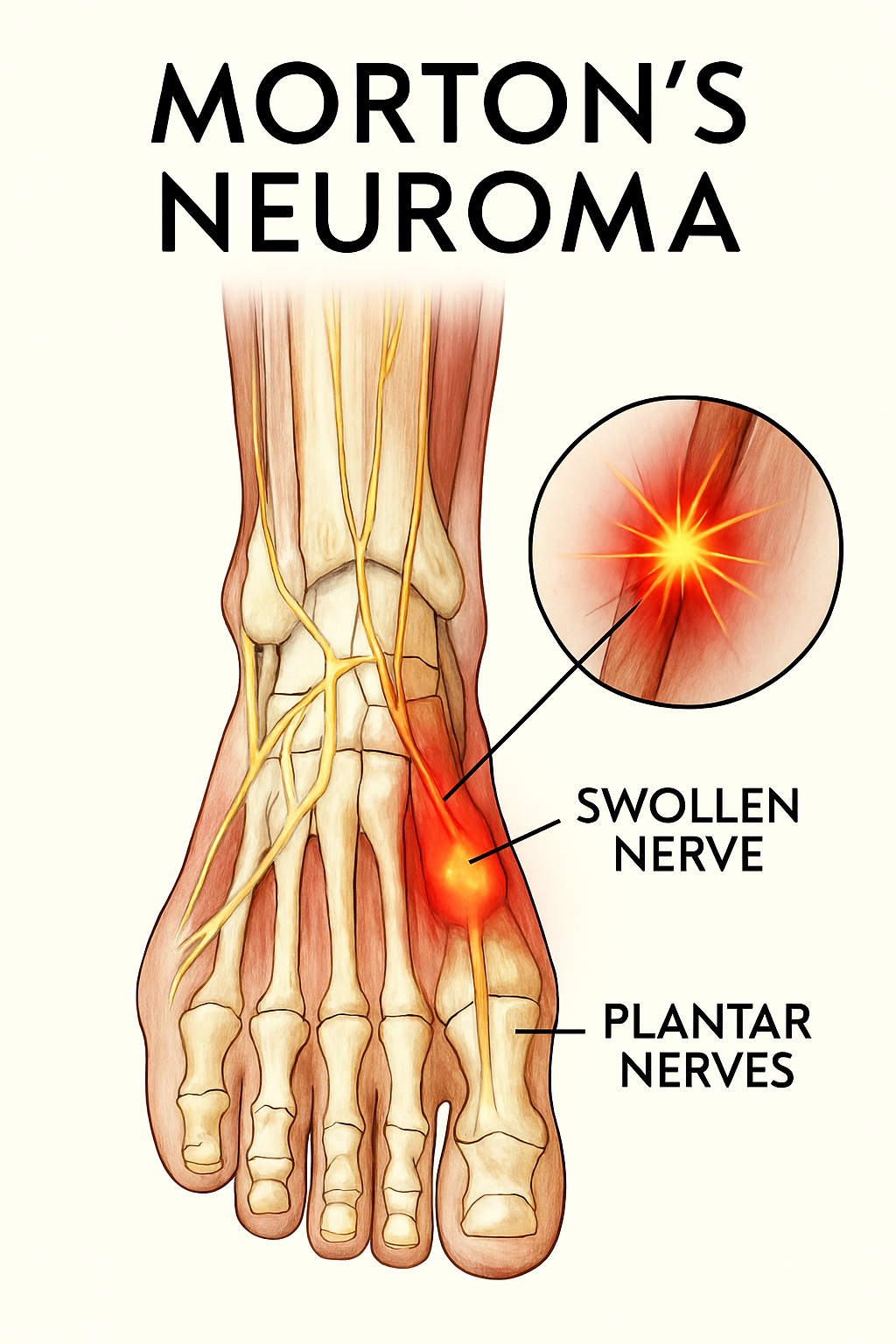

Morton’s Neuroma

Description

Morton’s Neuroma, a common overuse injury in runners, is entirely preventable. It is caused by repeated compression or irritation of a nerve between the metatarsal bones of the foot, leading to thickening and inflammation of the nerve tissue, most often between the third and fourth toes. Runners typically describe the pain sensation as stepping on a hard pebble with each stride.

The condition is often triggered by tight or narrow footwear that restricts natural toe splay. High-impact activities like running can aggravate the nerve, causing radiating pain, tingling, or numbness in the toes, especially during long runs or prolonged standing.

In addition to footwear and forefoot pressure, foot deformities such as flat feet or high arches can contribute to nerve irritation. If left unaddressed, these issues may lead to biomechanical imbalances like overpronation, further increasing the injury risk. Morton’s Neuroma is more commonly seen in women over 40, often due to extended use of narrow-fitting shoes.

Diagnosis is typically based on symptom history and physical tests like forefoot compression. Early diagnosis and intervention are key to managing the condition effectively. Imaging such as MRI or ultrasound may be used to confirm nerve thickening and rule out other causes.

Prevention and Healing:

- Footwear: One of the most effective ways to prevent Morton’s Neuroma is by choosing shoes with a wide toe box and proper cushioning. Avoid high heels and narrow-fitting styles, as these can contribute to the condition.

- Modify Your Run: Forefoot striking can aggravate symptoms. Transitioning to a midfoot strike may reduce impact on the Neuroma. However, this requires slight adjustments in running form to engage stabilizing muscles, which are crucial for maintaining balance and preventing excessive pressure on the forefoot.

- Orthotics: Use metatarsal pads or custom insoles to offload pressure from the affected area.

- Manual Therapy: Ice packs and massage can help reduce inflammation and pain.

- Medical Intervention: Cortisone injections may offer relief. Surgery is considered only for persistent, non-responsive cases.

Cruciate & Cartilage related Running Injuries Over 40

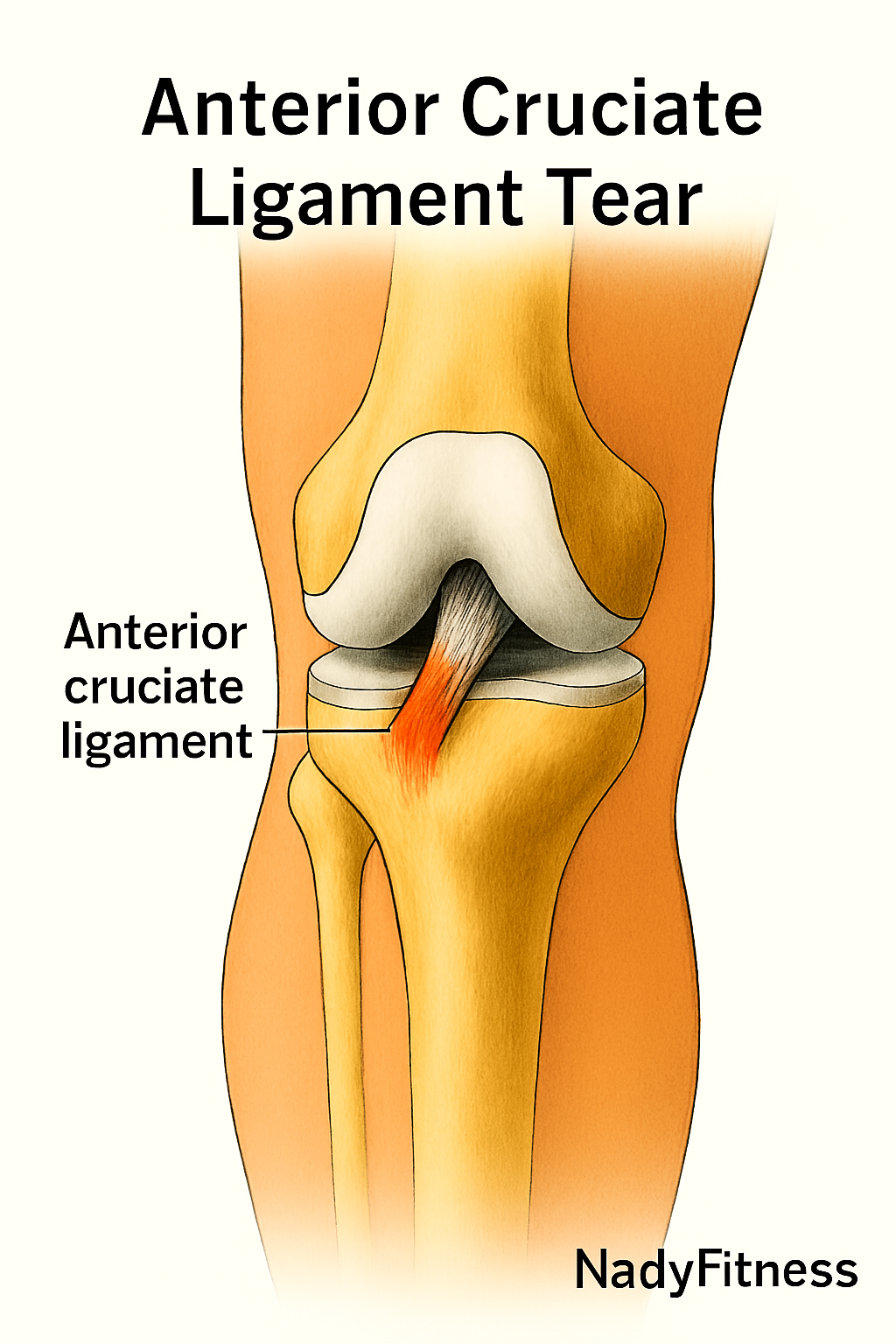

ACL Injury (Anterior Cruciate Ligament)

Description

Injury to the ACL is usually followed by a popping sound in the knee, usually triggered by an awkward landing or extreme pivoting of the knee joint. It is a painful injury that comes with other symptoms like swelling and walking instability. Your knee will not be able to bear your body weight properly. You may be able to identify this injury if you feel that your knee is “giving way” and if you feel the pain when you make lateral movements and while turning. However, it is recommended that you confirm your ACL Injury with an MRI scan or Lachman test.

An ACL injury typically occurs during awkward landings, sudden pivots, or rapid changes in direction. It’s often accompanied by a distinct popping sound in the knee, followed by intense pain, swelling, and instability. You may find it difficult to bear weight on the affected leg, and experience a sensation of the knee “giving way”, especially during lateral movements or while turning. Diagnosis is best confirmed through an MRI scan or a Lachman test, which assesses ligament integrity.

Prevention and Healing:

- Grade I–II sprains are mild to moderate injuries. You may need a brace for walking support during the initial recovery phase. Rehabilitation should focus on quadriceps strengthening and proprioception drills to restore joint stability.

- Grade III tears are severe and often require surgical reconstruction. Most individuals return to running within 6–9 months post-surgery, depending on rehab progress. Recovery typically includes gait retraining (often with an anti-gravity treadmill), progressive loading, and modalities like INDIBA® therapy to accelerate tissue healing.

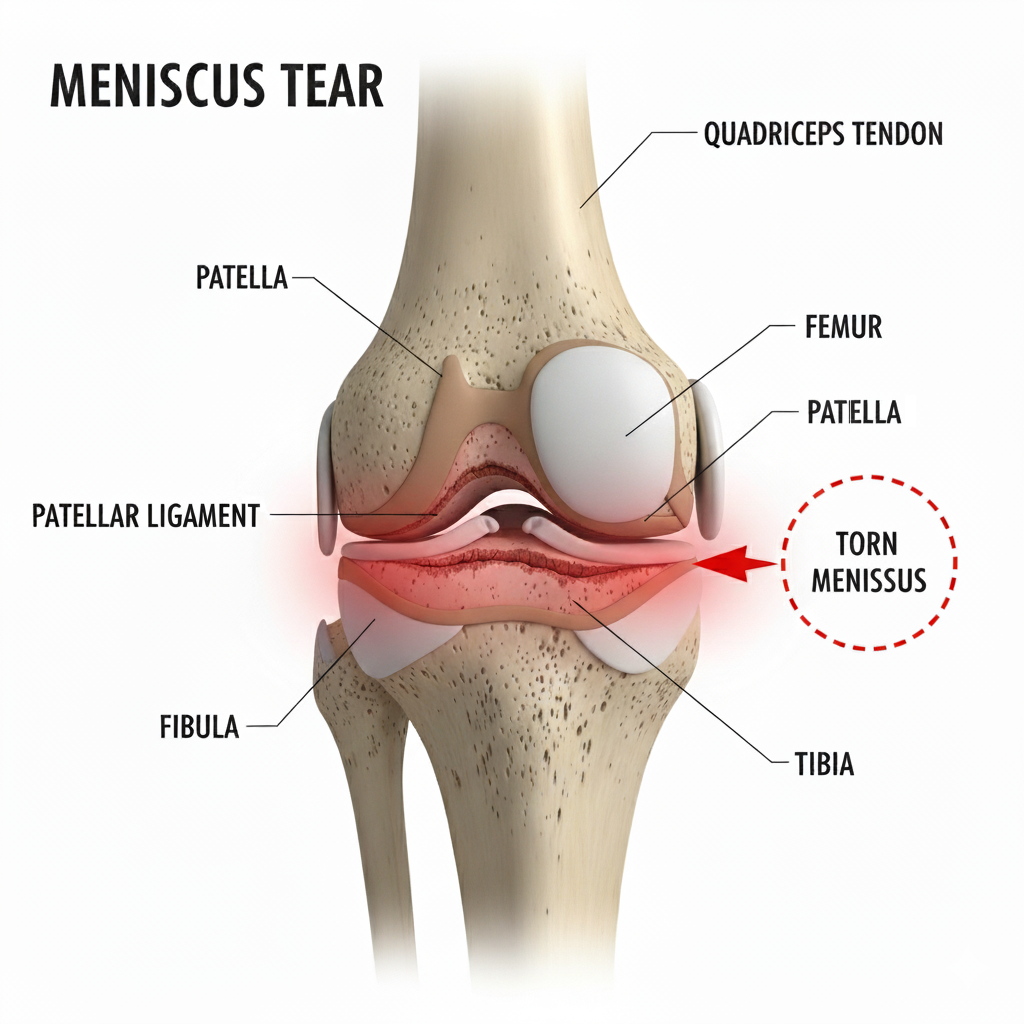

Meniscus Tear

Description

A meniscus tear is a common knee injury in older adults, often caused by damage or degeneration of the cartilage that cushions the space between the femur and tibia. Loss of this shock-absorbing cartilage tissue can lead to symptoms such as pain, stiffness, swelling, and reduced mobility. Degenerative tears are especially common in runners over 40. You may also experience locking, freezing, or crackling sounds during movements like squats.

Each knee contains two menisci (medial and lateral), crescent-shaped cartilages that absorb impact and stabilize the joint. Injuries to these structures can range from minor wear to complete ruptures. Meniscus tear often occurs due to overload on the cartilage during abrupt stops, sudden twists, or repetitive stress. Diagnosis is typically confirmed through a McMurray’s test or an MRI scan.

Prevention and Healing:

- Treatment varies depending on the severity and location of the tear.

- While people with minor meniscus tears can heal with rest and rehabilitation, severe cases may require reconstruction surgery.

- Minor meniscus tears may heal with rest, rehabilitation, and strength training.

- Degenerative tears often respond well to stability-focused exercises. Begin with low-impact activities like cycling or incline steppers before returning to running.

- Progressive loading must be approached cautiously to avoid relapse during meniscus rehabilitation.

- Acute tears may require surgical intervention, especially if instability or joint locking persists.

- In early rehab stages, avoid deep knee flexion exercises.

- Consistent, patient work is essential to restore the full range of motion – recovery may take several months to a year.

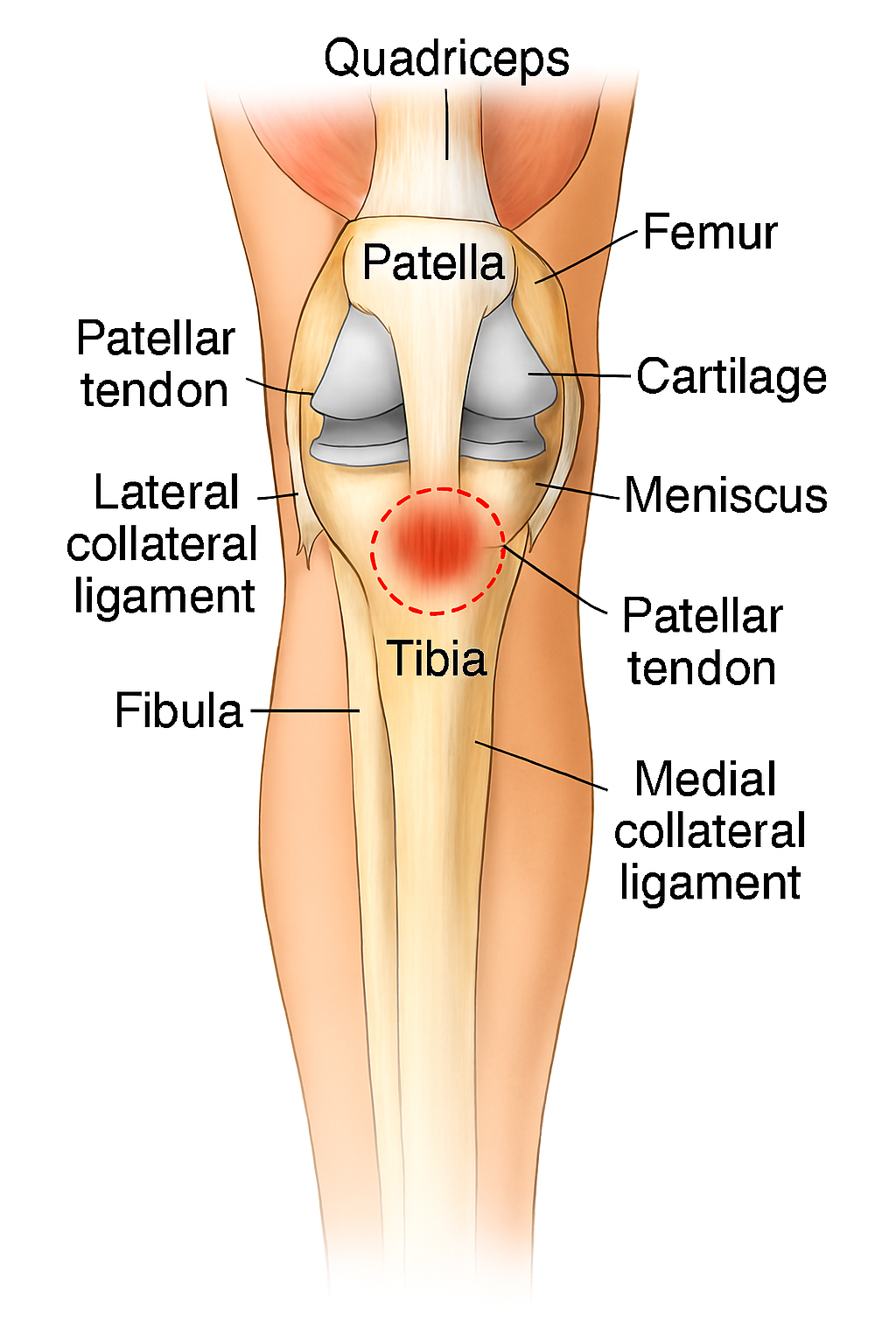

Patellar Tendinopathy (Jumper’s Knee)

Description:

Commonly known as Jumper’s Knee, patellar tendinopathy is an overuse injury affecting the patellar tendon – A thick tendon that connects the Shinbone to the knee cap (patella). It supports the transmission of force during knee extension activities like activities like squatting, jumping, or running. Individuals with Jumper’s Knee typically experience pain just below the kneecap, especially during activities that involve repeated knee engagement. The condition may start with gradual discomfort and the worsen to a continued strain.

In runners over 40, symptoms often develop gradually due to repetitive strain, not a single traumatic event. The condition stems from microtears and collagen breakdown, and recovery can be slow due to age-related tendon degeneration. You may experience stiffness after prolonged sitting and swelling or thickening around the tendon. The pain that eases during warm-up but worsens post-run.

Jumper’s Knee is more common after 40 due to reduced tendon elasticity and hydration. It can also be triggered by weak glutes, tight quads, or limited ankle mobility, all of which alter knee biomechanics and increase strain on the patellar tendon. A sudden increase in training volume or knee load without adequate recovery can also contribute to this condition.

Prevention and Healing

- Strength training with focus on glutes, quads, and hamstrings can help in improving knee stability and preventing Jumper’s Knee.

- Improve your mobility by stretching quads, calves, and hip flexors to maintain patellar tendon strength and range of motion.

- Avoid abrupt increases in mileage or intensity in your running sessions. Progress gradually.

- Use the right footwear with proper shock absorption and alignment.

- Rehab exercises for Jumper’s Knee include wall sits, clamshells, and eccentric quad work (Ideally under professional guidance).

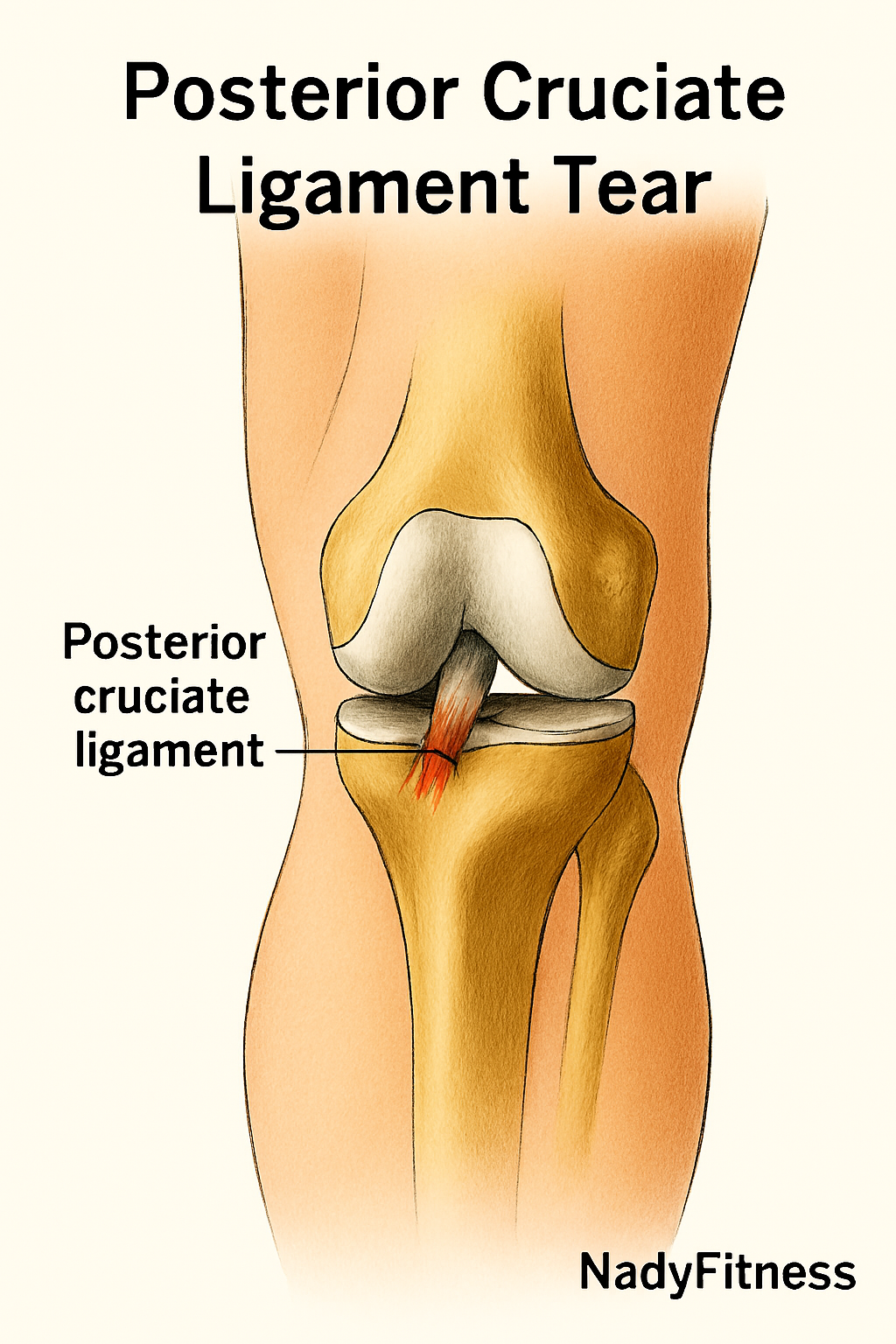

PCL Injury (Posterior Cruciate Ligament)

Description

The Posterior Cruciate Ligament (PCL) lies deep within the back of the knee joint. It plays a crucial role in preventing the shinbone (tibia) from moving too far backward relative to the thighbone (femur). PCL injuries typically result from high-impact trauma, such as falling onto a bent knee or during motor vehicle accidents. Unlike ACL injuries, PCL tears are less common among athletes. Symptoms often include swelling, instability, and discomfort, especially when walking downhill or descending stairs. Diagnosis is confirmed through a Posterior Drawer Test or an MRI scan.

Prevention and Healing:

- Most PCL injuries can be rehabilitated with targeted strengthening and balance exercises.

- Early detection supports faster recovery and improved knee stability.

- Rehab should be tailored to your biomechanics and the severity of the injury.

- Grade I–II injuries often heal without surgery, especially with focused quadriceps training.

- A brace may be needed to support daily activities and reduce instability.

- Avoid exercises that place excessive load on the hamstrings, which can stress the healing ligament.

- Grade III injuries typically require surgical intervention, especially if instability persists.

- Post-surgical rehab should emphasize quadriceps activation, proprioception drills, and controlled half-squats to restore function safely.

How to Avoid Common Running Injuries After 40

Seek Professional Help for Persistent Running Injuries

Listen to your body. If you experience ongoing discomfort or pain during or after running, consult a sports medicine specialist or physiotherapist and adjust your training plan based on their guidance. While rest is essential to kickstart the healing process, it’s not enough on its own. Rehabilitation plays a critical role in full recovery.

During rehab, mild pain may linger, but it should gradually subside as healing progresses. Understanding the difference between productive discomfort and harmful pain is key to injury prevention and long-term running success. We’ll explore detailed recovery strategies in our upcoming posts to help you navigate this phase with confidence.

Prioritize Warm-Ups and Cool-Downs to avoid Running Injuries

Start each run with dynamic stretching drills to activate your muscles and joints. After your session, follow up with static stretches to improve flexibility and reduce post-run stiffness. This simple habit can significantly lower your risk of injury.

Embrace Cross-Training to Sidestep Running Injuries

Incorporate low-impact activities like swimming, cycling, or elliptical workouts to strengthen underused muscle groups and reduce repetitive strain. Swimming, in particular, offers excellent upper-body conditioning to complement the lower-body demands of running.

Build Strength to Prevent Running Injuries

Strength training is non-negotiable after 40. Focus on compound movements that target the core, hips, shoulders, back, and lower legs to enhance stability and reduce injury risk. Runners with weak upper bodies are more prone to imbalances. Besides weight training, pull-ups, push-ups, chin-ups, and handstands are powerful additions to your weekly routine.

Dedicate Time to Stretching

Squats and lunges alone won’t release the deep muscle tension that runners accumulate. Schedule at least one weekly session focused solely on stretching. Modalities like yoga, calisthenics, and martial arts help to realign the body and prevent overuse injuries.

Wear the Right Running Shoes

Choose good-quality running shoes that offer proper arch support and cushioning. Replace worn-out footwear regularly to maintain optimal shock absorption and joint protection.

Running Injury Prevention Is Possible

Running after 40 can be deeply rewarding, physically and mentally. By staying informed and proactive, you can sidestep common running Injuries after 40 and keep moving with confidence. Injury prevention isn’t just a strategy; it’s a mindset that supports a lifelong, joyful running journey.

Disclaimer

Just because two injuries affect the same area doesn’t mean they share the same root cause. For example, pain in the leg might actually stem from the lower spine, as in the case of sciatica. Injuries can shake your confidence and make you feel like your body’s working against you – but healing from running injuries is possible. That said, if your recovery stalls or something doesn’t feel right, don’t push through it alone. A licensed medical professional can help you get clarity and the recommend the right care option you deserve.

Reference 1 | Reference 2 | Reference 3 | Reference 4 |